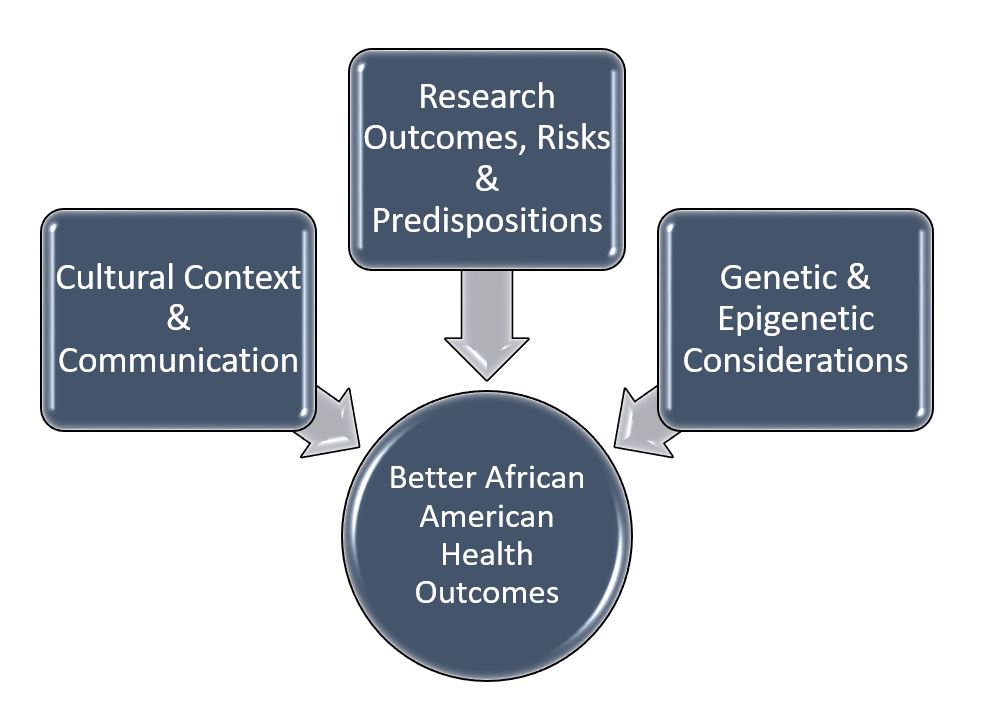

Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans written by Dr. Greg Hall is a landmark manual aimed at physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants that will outline specific differences in communication, clinical therapies, medications, protocols, and other critical approaches to the care of African Americans. The book takes a comprehensive approach to the clinical support of providers that see African Americans.

Because of the “patient-centered” movement in hospitals and insurance plans, providers are now financially impacted based on the quality of care provided to individual patients. African Americans have the worst medical outcomes of any racial/ethnic group in America including the highest mortality, longest hospital length of stay, worst compliance with medications and referrals, and the lowest trust of the healthcare system. The book, which is the first of its kind, is a major step in decreasing the numerous health disparities driven by physicians and other clinicians.

Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans

Primary Audience:

- Primary care physicians including Internal Medicine and Family Practice.

- Internal Medicine and Family Practice residencies

- Medical students on clinical rotations

- Physicians in urban and southern clinics, hospitals, and other medical settings that see a significant number of African Americans.

- Nurse Practitioner training and clinical rotations.

- Physician Assistant training and clinical rotations.

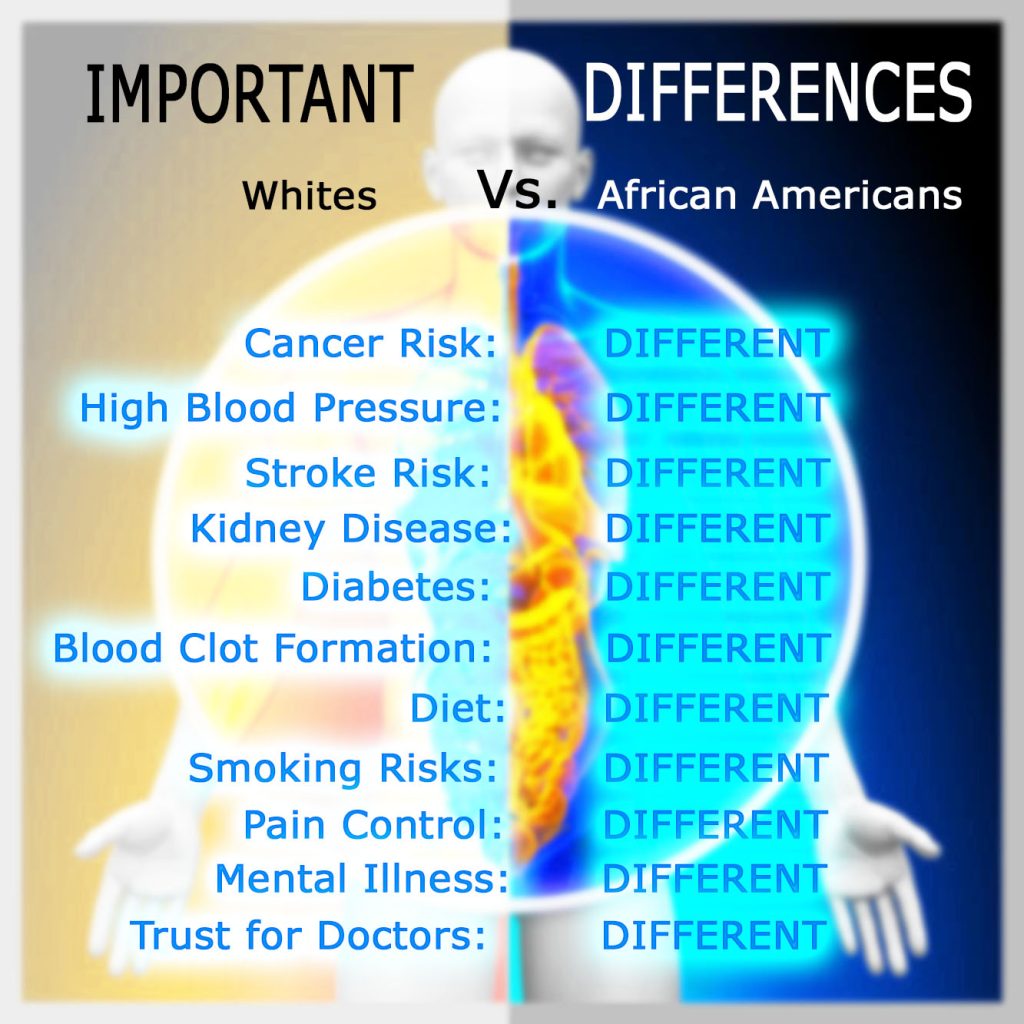

There are countless well designed studies that validates verified differences in the clinical care of a number of pervasive diseases in African Americans including hypertension, heart disease, kidney disease, obesity, cancer, and much more.

Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans reviews a number of important differences in the medical care of African Americans, for example:

- Two of the most common medications for treating hypertension (ACE inhibitors and beta blockers) are contraindicated as first line therapy for hypertension in African Americans, yet a recent study showed one third of African Americans with hypertension continue to be prescribed these medications which result in less optimal outcomes.

- The presence of a “salt-sensitive gene” called “lysine-specific demethylase” 1 (LSD-1) that occurs disproportionately in African Americans and impacts hypertension control and overall mortality.

- Lipid profile results ‘look’ more favorable in African Americans, yet the cardiovascular outcomes are worse . . . bringing into question the weight a lipid profile should receive in these populations.

- African Americans have twice the risk for stroke and a higher risk for bleed with anticoagulation, and frequently require higher doses of warfarin (than White Americans) to achieve a therapeutic response.

- The approach to anticoagulation with Warfarin and risk of thrombosis is substantially different in African Americans and impacts outcomes.

Colon cancer screenings are consistently delayed in African Americans due to provider’s adherence to majority population recommendations. Colon cancer screening is recommended to begin at age 45 in African Americans due to higher incidence of more aggressive cancers in these populations.

Colon cancer screenings are consistently delayed in African Americans due to provider’s adherence to majority population recommendations. Colon cancer screening is recommended to begin at age 45 in African Americans due to higher incidence of more aggressive cancers in these populations.- One common colon cancer screening procedure, sigmoidoscopy, is not recommended in African Americans due to its potential to miss pre-cancerous polyps in that population. Physicians continue to send African Americans for this contraindicated procedure due to their lack of knowledge of this nuance in care.

- One third of the African American population has a gene that will greatly increase their risk for kidney failure and the need for dialysis, and this gene is completely absent in White Americans.

- Salt sensitivity occurs in 70 percent of African Americans but only 22 percent of White Americans with hypertension. The Food and Drug Administration recently established separate recommendations, based purely on race, to more rigorously restrict salt in older individuals and ALL African Americans regardless of age. Few providers know to stress the benefit of salt restriction in African Americans.

- The Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA), a screening test for prostate cancer, is more reliable and predictive of prostate cancer in African Americans compared to other ethnic groups, yet its use has decreased in all populations.

Physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants do not intentionally provide inferior care to African Americans, they simply provide clinical care based on majority population best-practices. The value of the Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans is it gives best practices for African Americans. Because African Americans tend to go to providers and hospitals in urban areas and in the southern states, providers that see African American patients usually see a significant number. African Americans, being 13 percent of the US population, do not usually make up 13% of the usual clinical practice. Because 60 percent of all African Americans live in just 6 states, providers that see Africans Americans see a much higher percentage than the national average, and many see over half of their practice composed of African Americans.

Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans Can Improve Mortality Differences

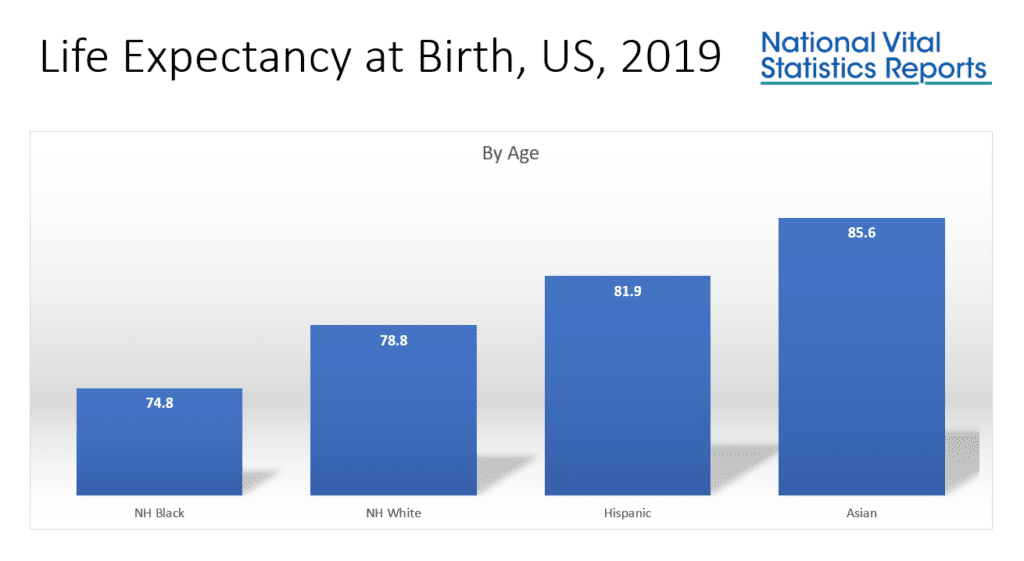

Health disparity outcomes are usually grouped as “minorities” versus “Whites” and the argument is that these special populations need added attention as a group, but the reality is African Americans alone have the most dramatic differences, and any interventions aimed at making a palpable difference need to be African American-specific and not diluted as merely for “minorities”. The death rates for Hispanic/Latinos, American Indian/Alaskans and Asian Pacific Islanders are all lower than White Americans. The only true mortality disparity relates to African Americans.

Disease burdens vary greatly among minorities with African Americans having a completely different list of clinical predispositions as compared to Hispanic/Latinos, or Asian Pacific Islanders. A book broadly addressing the clinical differences of minorities as if they are similar will frequently miss the mark. The similarities that are assumed are frequently those of healthcare access and poverty concerns. Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans looks at clinical differences based on race/ethnicity . . . not socio-economic status or vulnerability.

There are nuances in the care of African Americans that can be used across socioeconomic classes. Differences in screening, prevalence of diseases, medication effects, and more are altered based on race/ethnicity, not income. More affluent African Americans still have inferior outcomes, not based on their insurance, but instead on these differences that drive clinical outcomes. Most providers for African Americans simply do not have a resource for the focused information about these important differences, and the disparities data based purely on race proves it.

As the first comprehensive book on the clinical care of African Americans that broadly addresses all of the considerations related to a patient’s health including differences in historical perspective, communication, bias, disease demographics, and clinical therapies and approaches; this book will make a difference in African American quality outcomes.

With his unique perspective as a public health and health equity advocate, public insurance adviser, educator/lecturer in medicine, hospital leadership representative, and primary care physician, Dr. Greg Hall has pulled together a resource that addresses the needs of the provider, the hospital, insurances, and the greater public good.

Based on the success of his book, Pri-Med, a national medical education company has begun a webcast featuring Dr. Hall. During “Bridging the Gap: Conversations with Dr. Hall” he reviews the latest issues in healthcare related to disparities and delivering equitable healthcare. The series was awarded “Best Practice in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” by the National Association of Medical Education Companies.

Colon cancer screenings are consistently delayed in African Americans due to provider’s adherence to majority population recommendations.

Colon cancer screenings are consistently delayed in African Americans due to provider’s adherence to majority population recommendations.