A Black Doctor Needed Pain Medicine and Didn’t Get It

When I suffered from appendicitis a few years ago, I was admitted to the hospital and had emergency surgery. I woke the next day with all sorts of tubes and IVs. They had clearly saved my life, which I appreciate to this day. But, the most prevalent thing I can remember about those times was the severe abdominal pain I had after the surgery. As a physician I worked in the hospital every day but, I had never been admitted to the hospital as a patient. This was a new perspective and experience I will never forget.

The Pain Medicine Didn’t Work for Me

The surgeon had ordered an intravenous pain medication which I was to get every four hours. Because I was in such severe pain, I wondered whether the nurse had actually given the medication after I woke up. Upon asking, she confirmed that she had. I lay there and suffered for another three hours and then again requested pain medicine that I thought would help better than the last time. The nurse administered the pain medicine, and this time I noted a severe cramping pain that built to a crescendo of severe pain. I began to think to myself, is this pain medicine causing my worsening pain? I brushed off this seemingly silly thought and waited another four hours for an additional administration of pain medicine.

After another request, the nurse again administered the same medicine, and again, I had an increase in my pain from 9 out of 10 to what my patients would say is a 20 out of 10, which up that that point in my life I never understood why the “out of 10” was ignored so readily. I then told the nurse I needed something different for my pain because what she was giving me was not only not helping, it was making my symptoms worse. She looked at me with a look I had never gotten in my life. The look that I was a “drug-seeking patient.” Now on the defense, I told her that I had never been on any pain medicine in my life. I explained that I didn’t even take the pain medicine my dentist gave me when they pulled my wisdom teeth. She nodded with a “I don’t believe you” look, and left the room.

“Drug Seeking Doctor?”

I wondered how this nurse could know that I was a physician, know that I trained at a prestigious hospital, know that I taught at a medical university, know that I just had major surgery just hours earlier, yet still see me as drug-seeking. There was only one answer.

As it turns out, my experience was not a unique one.

Differences in the Treatment of Pain in African Americans

With the added burden of worse disease outcomes and premature death due to a myriad of health problems in African Americans, it is no surprise that there is also a significant racial disparity in the treatment of pain. Whether it is due to access issues and insurance, bias and discrimination in the healthcare system, or poor quality communication with their clinicians, African Americans are more likely to have whatever pain they have go under-treated or untreated. Based on a number of studies, African Americans are more likely to have their pain discounted or underestimated, and less likely to be screened for pain. Despite my being a doctor and no indication in my chart that would suggest I might get addicted, the nurse discounted my complaints and saw me as “drug-seeking.”

Unequal Treatment Continues

The unequal treatment of pain in African Americans span their lifetime. A study of nearly one million children diagnosed with appendicitis revealed that, relative to White American children, Black children were less likely to receive any pain medication for moderate pain, and were less likely to receive opioids for severe pain. African American adults with identical joint surgeries having demonstrably decreased pain treatment. As Anderson and colleagues found in their study “Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care.”

“This review reveals the persistence of racial and ethnic disparities in acute, chronic, cancer, and palliative pain care across the lifespan and treatment settings, with minorities receiving lesser quality pain care than White Americans.”

Black Patients Less Likely to Get Pain Medicine for Similar Symptoms

Another study involving a medical record review of equal pain symptoms in racially matched patients found African Americans with lower rates of receiving pain medications, and the cause was ultimately attributed to physician discretion . . . which means physicians have the “freedom to decide.” Unfortunately, this “freedom to decide” is where many African Americans get the short straw.

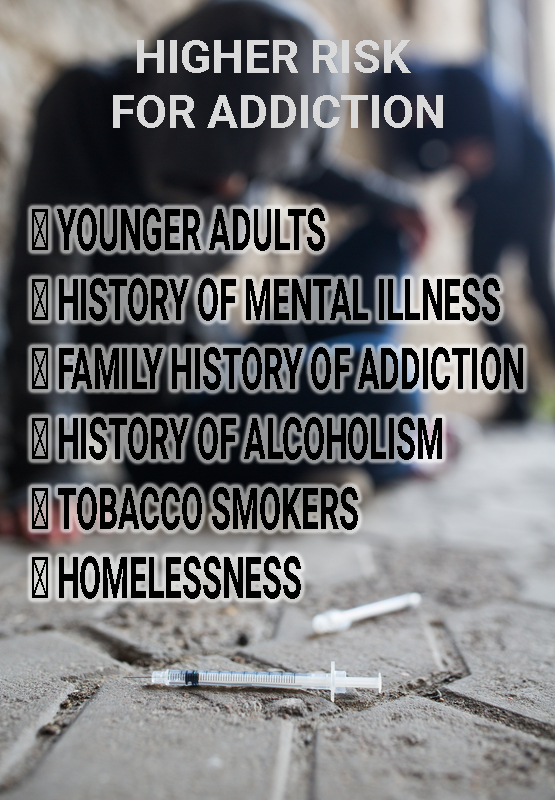

In my case, it was nursing discretion because it took multiple more hours for the nurse to tell my surgeon, who then promptly changed my medication. Doctors and nurses report concerns about addiction as their main reason for not starting or increasing pain medicine, and addiction is a real problem in the US, but there are ways to predict if a patient is at risk for addiction.

Make no mistake about it, the opioid crisis is real and incredible deadly as I have written in another article. And clinicians need to be careful to not add another addict to the already out-of-control numbers. My issue here is the disparities, or differences, in our CURRENT pain treatment. Leaving someone in pain when a treatment is available is incredibly cruel and physicians should err on the side of compassion as well as follow science which clearly dictates the type of patient at increased risk for addiction.

What Should I Do?

As patients, we have just as much a right to have our pain treated as anyone else. Having our pain needs under-treated or untreated is unacceptable given all of the options for pain treatment. You can call the hospital’s ombudsman, who should advocate for all patient’s rights. You can request a provider change, be it a nurse or physician.

Collectively, we need to ensure that our medical needs are met in an equitable yet safe manner.