There are racial disparities in sleep with African Americans having a shorter sleep duration, a harder time falling asleep, and a tendency to wake up more easily after falling asleep. There is also a decreased ability to phase shift African Americans sleep cycles when exposed to jet-lag and shift work situations, and the total duration of the cycle was smaller, a study by Eastman and colleagues at Rush University Medical Center found. Sleep differences in African Americans cause a good deal of suffering.

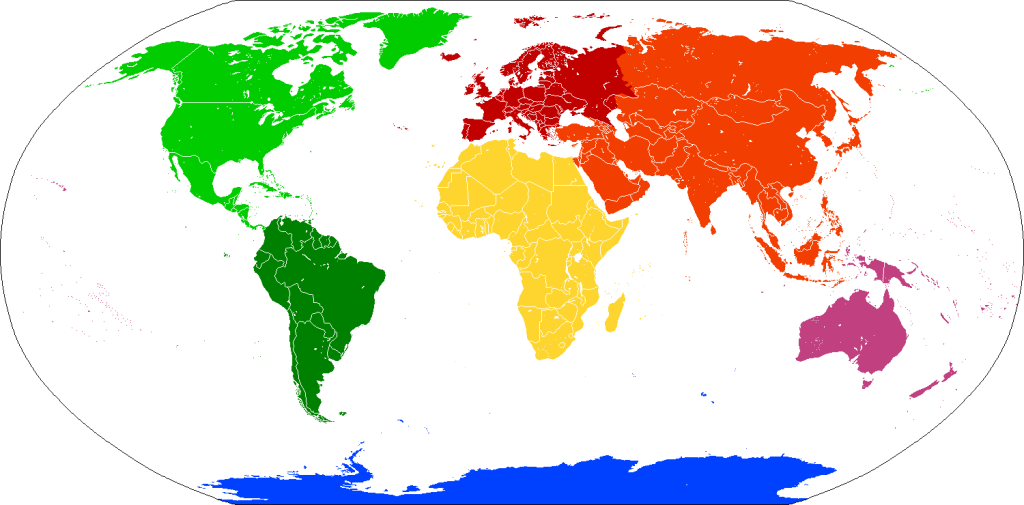

These researchers surmised that the differences in sleep architecture grew from thousands of years of genetic modifications resulting from, for African Americans, exposure to year-around consistent 12-hour light-dark cycles, versus whites coming for northern regions with significant variability in the day length, dawn, and dusk times.

For example, in Ohio the day length changes from as short as eight hours in the winter to as long as sixteen hours in the summer. Ohioans are constantly adjusting to time shifts. With thousands of years of exposure to time changes, Ohioans would develop an increased ability to tolerate the changes. Closer to the equator (like western Africa), the time doesn’t shift nearly as much. The days are 12 hours long all year and there is no need to have an ability to tolerate time shifts.

Therefore “the shifting circadian periods in non-equatorial regions left a genetically modified increased tolerance for variable light-dark productivity hours.” Put simply, people who genetically come from regions near the equator are less able to adjust to time shifts, daylight savings times, jet lag, or anything else that causes a shift in sunrise and sunset.

Everyone has a “circadian period” which is an innate sleep wake cycle. We also have an ability to shift that cycle somewhat. People whose genes come from northern areas of the earth (Europe, Canada, etc.) have an ability to tolerate shifts in time whereas those of us from Caribbean, African, South American regions have much more difficulty adjusting.

In another study, researchers exposed African Americans and White Americans to a 9 hour delayed light/dark sleep/wake and meal schedule, similar to traveling from Chicago to Japan. Essentially what would take 10 days for full adjustment in White Americans, would take 15 days for African Americans to adjust.

Swing shifts are bad for your health!

The need to adjust to time zone changes is only occasional in most people, and there are methods to make this adjustment smoother, but shift work seen in factory workers, police and fireman, healthcare staff, and other positions place an additional health burden on these workers. Shift working was found to add an additional 40 percent risk of heart disease as compared to non-shift work.

There is also increased weight gain as a result of decreased glucose tolerance from meals consumed in the night. When eating at night, your body tends to store more of the calories rather than burn them. Therefore night workers (who have to eat sometimes) tend to be more overweight. Researchers have also found that shifts workers have worse cholesterol results.

All of this contributes to increased health problems and premature death.

Shift work is more prevalent in the African American community and is also associated with worse health outcomes including:

- increased smoking

- elevated blood pressures

- obesity

- increased alcohol use

- decreased physical activity

- depression

- work stress

By incorporating a planned exercise schedule and diet, emphasizing the dangers of smoking (particularly in shift workers), and providing better insight into the social impact of these schedules, can help many shift workers. The few individuals that continually fail to adjust to shift work may feel better knowing there is a simple explanation for their troubles.

It’s in their genes.