Topic: Trust in Healthcare

African Americans Are Not Getting Their Pain Adequately Treated

A Black Doctor Needed Pain Medicine and Didn't Get It When I suffered from appendicitis a few years ago, I was admitted to the hospital and had emergency surgery. I woke the next day with all sorts of tubes and…

Establishing Trust When Patients Distrust Doctors

Distrust Doctors ?? Multiple studies over an extended period of time confirm what most doctors and providers already knew, African Americans are more likely to distrust doctors and other healthcare providers than patients of other racial or ethnic groups. What…

African American Healthcare Negatively Impacted by Bias-Driven Data

Hospitals across this nation use protocols and algorithms aimed at improving outcomes in their patients, but because of nuanced differences in the care of African Americans, those protocols have now been shown to negatively impact African American healthcare. A recent…

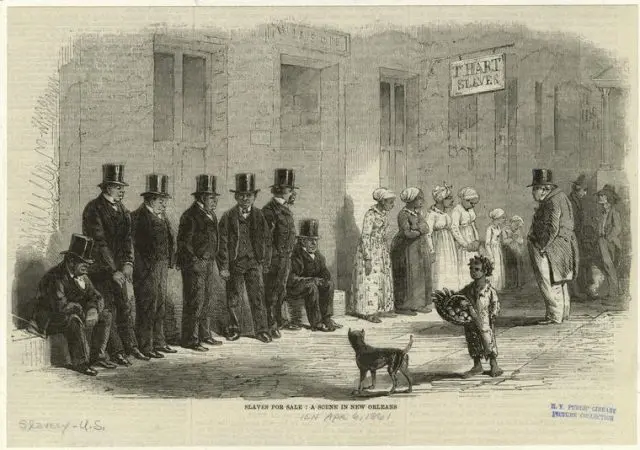

Historical Reasons for African American Distrust of Doctors

Stephen Kenny, University of Liverpool The history of human experimentation is as old as the practice of medicine and in the modern era has always targeted disadvantaged, marginalized, institutionalized, stigmatized and vulnerable populations: prisoners, the condemned, orphans, the mentally ill,…