Topic: Patient Education

African Americans Need to Walk More! More Daily Steps Tied to Better Overall Health

Regular exercise has always been associated with better health. Still, with newer smartphones, watches, and “wearables,” we can now measure more accurately how much walking and exercise we get in a day. Unfortunately, we in the Black community do not…

Low Potassium and African Americans

Potassium doesn’t get enough credit as a very beneficial nutrient to good health and potassium deficiency (low potassium) has been directly related to high blood pressure, heart problems, diabetes, muscle weakness, fatigue, and much more. Multiple studies have confirmed that…

Multivitamins May Help African Americans Avoid Alzheimer’s Dementia

A new study is showing benefit from taking a multivitamin once a day in slowing the progression of dementia in older individuals. It has long been known that vitamin D deficiency is directly linked to Alzheimer’s Dementia and African Americans…

Do Sound Machines for Sleep Help?

There is definitely a science to sleep and why sounds can both improve or interrupt a good night’s sleep. The internet is filled with people who report greatly improved sleep with sound producing devices, long-playing internet videos, and other media. …

A Doctor’s COVID Experience

I caught the coronavirus in November 2020 and here I tell the story of my illness. Don't risk getting this virus. Get vaccinated.

The Best Multivitamins for African Americans

Which multivitamin should I take? As a physician, I get this question multiple times a day, every day. And the answer would frequently depend on who was asking. Are they younger or older? Male or female? How is their diet? …

Diabetes Differences in African Americans

There has been some startling discoveries lately in the differences in how diabetes is diagnosed and treated in African Americans. Because of genetic nuances that we normally may ignore as insignificant, hundreds of thousands of African Americans remain under-diagnosed and…

Heavy Smokers at Higher Risk for Diabetes

African American smokers have a higher risk for diabetes A large study consisting of over five thousand African Americans found that those African Americans who smoke more than a pack of cigarettes in a day were at increased diabetes risk. …

Lactose Intolerance in African Americans

Three out of four African Americans are lactose intolerant. Lactose intolerance means that if you drink milk, eat yogurt, have cheese, or any other dairy-based product in large amounts, your digestive system will have difficulty digesting it. Most people report…

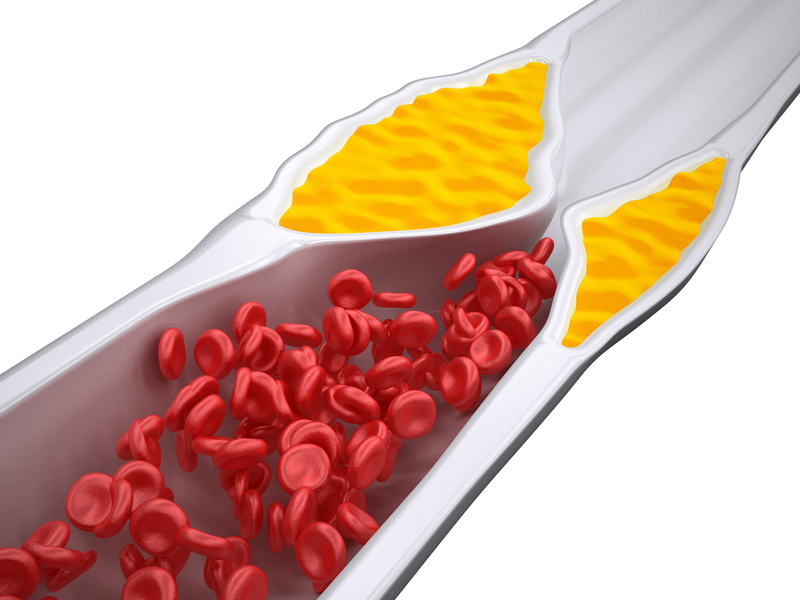

Is Cholesterol Lowering Medicine Bad for You?

Many of my patients have high cholesterol and are on cholesterol lowering medicines called statins like Lipitor (atorvastatin), Zocor (simvastatin), and Crestor (rosuvastatin). Occasionally they will come in saying some well-meaning friend told them that "cholesterol medicine is bad for…